A good read - so far anyway. I've been reading this on and off over the last few weeks and I'm about halfway through.

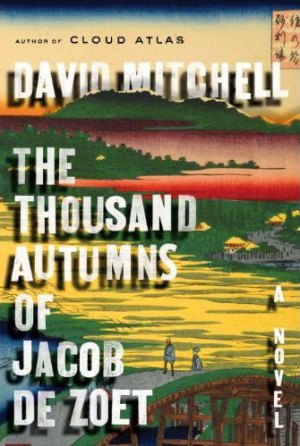

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet is an enjoyable, well written, dense (but not impenetrable) novel set in Eighteenth Century Japan on the tiny western foothold of the guarded island of Dejima in Nagasaki Harbour. Home of the traders of the Dutch East India Company.

I had previously read only one of David Mitchell's novels Black Swan Green, which like this is fairly straightforward in terms of it's narrative. Whereas he is generally known for his more narrative bending efforts in his previous novels Cloud Atlas and Ghostwritten.

I guess this novel has also just made it to the Booker Prize long list and so will undoubtedly become more popular.

Mitchell is quite a wordsmith. I enjoy the way he plays with word and language and does so in a way that appears effortless. I read one comment on this book where a reader/reviewer complained about the anachronisms in it - with made me laugh out loud. A "historical novel" is basically just one big anachronism so it seems a bit of a waste of time to actually note them as you go along and then complain about them. In fact one thing I enjoy about The Thousand Autumns is the role of interpreters in it. They are fairly central to the story as they were central to the lives of both the Dutch Traders, Japanese Merchants and Japanese authorities involved with the combination of commerce and protecting Japan from the threat of Western influence. But if course everyone in the book "speaks" English. So there will be a Dutchman helping a Japanese translator find the right words to translate a phrase correctly from Dutch to Japanese - but all done in English. As are also mistakes in translation caused by different but similar sounding words or words with two different meanings - all of which are again in English. Yet you come away from reading such a passage convinced you read/heard it in Dutch and Japanese!"The year is 1799, the place Dejima in Nagasaki Harbor, the “high-walled, fan-shaped artificial island” that is the Japanese Empire’s single port and sole window onto the world, designed to keep the West at bay; the farthest outpost of the war-ravaged Dutch East Indies Company; and a de facto prison for the dozen foreigners permitted to live and work there. To this place of devious merchants, deceitful interpreters, costly courtesans, earthquakes, and typhoons comes Jacob de Zoet, a devout and resourceful young clerk who has five years in the East to earn a fortune of sufficient size to win the hand of his wealthy fiancée back in Holland.

But Jacob’s original intentions are eclipsed after a chance encounter with Orito Aibagawa, the disfigured daughter of a samurai doctor and midwife to the city’s powerful magistrate. The borders between propriety, profit, and pleasure blur until Jacob finds his vision clouded, one rash promise made and then fatefully broken. The consequences will extend beyond Jacob’s worst imaginings. As one cynical colleague asks, “Who ain’t a gambler in the glorious Orient,with his very life?”" (Official book blurb)

I listened to a radio interview with Mitchell, who lived in Japan for a number of years, and when announced to his Japanese wife (they now live in Ireland) that he was going to write his "Japanese novel" she said that if he wrote another noble Geisha potboiler type novel she would stab him with a very large knife! Luckily she must have considered that The Thousand Autumns passed muster.

Anyway here's some clips from a review. And as I said it is an interesting, enjoyable and intelligent read with enough of a challenge to it that you probably wouldn't want to take it to the beach.

From Charles Foran's review in the Globe and Mail:

"...Jacob de Zoet lies in between the sprawling, mind-altering Cloud Atlas and the controlled, sensitive Black Swan Green. It is a straightforward historical novel, told chronologically and in vivid present tense. Mitchell, who recreates entire worlds with such ease one could be forgiven for assuming that he time-travels to them, and then returns to report on what he has observed and heard (in multiple tongues), moves with no less apparent effortlessness from perspective to perspective.

Jacob’s point of view dominates early on, but there are scenes set among the Japanese themselves, including sequences in a remote mountain nunnery where women are imprisoned as sex slaves. A thrilling narrative shift in Jacob de Zoet centres around that nunnery, and the novel moves away from its should-be lovers, widening out to address the emerging global politics of 19th-century imperialism. How it reconciles them in the elegiac final pages is beautiful and despairing, a quiet, perfect note on which to end.

That ending, a string of failures of “contact,” with the disappearance from history of the story’s protagonists as certain as the vanishing of Dejima itself, is deeply felt. Often overlooked by admirers of Mitchell’s daunting formal skill is the humanism, empathetic and moral, that informs his fiction. An English naval captain endures an outbreak of gout while he attempts to do his empire’s bidding in Nagasaki Bay, affecting his decisions; a Japanese magistrate, learning of an unspeakable cruelty going unchecked, ends it in the only way possible – by sacrificing his own life.

In Cloud Atlas, the theme of predation, the tendency of organisms to prey upon each other to mutual ruination, unified the six separate narratives. In Jacob de Zoet, this preoccupation is evidenced in the careful construction of the various small, overcrowded prisons – islands, nunneries, ships, homes – inside of which the characters must operate. “Why must all things,” the same gout-ridden captain laments, “go around in stupid circles?”

A writer as naturally curious, generous and able to translate an acute perceptivity to, and wonder at, the natural world as David Mitchell isn’t likely to produce a hushed, low-key novel. For some, Black Swan Green was even a little muted: Mitchell with the volume kept too low on his singular voice – or, rather, his glorious voices. Though direct in its storytelling, Jacob de Zoet marks a return to full amplitude. That means occasionally over-long scenes and one or two rambling monologues. But it also guarantees fiction of exceptional intelligence, richness and vitality"

No comments:

Post a Comment