There is a lovely book of photographs by Stephen Shore called the

Gardens at Giverny. It is very nicely done and has always been a favourite of mine. But I wonder at the conflicting emotions when the Metropolitan Museum of Art suggested photographing Monet's newly restored house and gardens at Giverny.

Holy crap - what an incredible opportunity - to photograph Monet's Gardens. Holy crap - how on earth do you photograph Monet's Gardens.

The end result is a book that I feel reflects that. It is a beautiful collection of photographs giving us Shore's vision of the renascence of these iconic gardens, showing us their hidden and unnoticed details and late summer parched browns as well as their verdant lushness. A well executed collection of pictures by a major photographer. (I know of one landscape architect who keeps a copy on her desk. I also found, while looking for online pictures from it an interview with Stephen Shore where he notes that the contemporary photographer he is most interested in is

Walid Raad which I find most encouraging in the light of what I say below).

And yet... and yet, place one or even all of these photographs beside one of Monet's paintings of his garden and they would be, I believe, immediately eclipsed (though I haven't actually stood, book in hand, before

Water-Lilies or

The Water-Lily Pond at the National Gallery). Certainly in many ways it's an unfair comparison, and I'm sure it was a comparison that Shore was both aware would be made and was probably constantly aware of in himself while he worked. But there is almost no other way it can be. Which brings me to what I see as the heart of the problem of photography - what I recently referred to as

sustaining our gaze.

(Water-Lilies, Claud Monet)It is one of the fundamental problems of photography that photographs rarely seem able to hold our attention for an extended period of time, never mind sustain our concentrated gaze. I find it hard to think of almost any photograph that is capable of holding a viewers gaze for even thirty minutes, never mind an hour or two or a whole afternoon. And yet I can think of numerous other works of art that can do just that.

When encountered, even a painting by a less than well known 18th Century artist - such as

Gordale Scar (A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale) by

John Ward can hold our direct attention for quite some time. And yet go to an exhibition of work by say Robert Adams or Eggleston or Lee Friedlander and how long would we spend, with our gaze fixed on an individual picture? Ten minutes? Twenty minutes, thirty? I think that would be approaching unusual even for the photographically literate, to say nothing of the serious but non specialist general viewer. Possible, but rare.

(Gordale Scar (A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale) by John Ward)

And what of travelling to see a photograph? A single photograph mind you, not a whole exhibit of a photographer's work. I can think of a good number of works of art - mainly, though not only, paintings - that I would make the time and effort to travel some way to see - to another country even (and on occasion have done so). But to do the same for a single photograph? There are less than a handful of photographs that would have the same draw (a particular Atget - tiny as it would be; possibly a Walker Evans. Maybe even something like an early Fox Talbot). For a major exhibit of a particular photographer's work, certainly I would make the effort. But for individual photographs it is hard to think of many at all.

(Parc de Scaux, Atget)Now none of these or the following thoughts are terribly new or original, but what has prompted me to start putting them together is a growing dissatisfaction with so much of the work I see that crosses my desk almost every day in one way or another. Yes, there is all sorts of work that excels at what it is trying to do. Work that adds another little twist or tweak to a certain direction or area of photography and does so well, whether it be large format urbanscapes, deadpan portraits, large format prints, directed and arranged tableaux etc. etc. And yet almost none of it even begins to push up against what I feel are the current, long standing limitations on photography (but

not inherent limitations, because I don't believe they are).

(from Sticks and Stones - Lee Friedlander)This is what has been called

"the problem of photography", and the limitation of the gaze, the holding of our attention, is the clearest symptom of the problem. As I see it there are three main causes to the problem, three main limitations, three boundaries, that photography has yet to make serious - or at least successful - attempts to break out of (and which is where I feel that so much contemporary work is lacking. I encounter little which is even pushing up against these boundaries, never mind making an effort to break through them or smash them out of the way completely).

I want to take some time in future posts to explore these boundaries and the ways they limit or restrict photography, but for now the three boundaries as I see them are:

1.

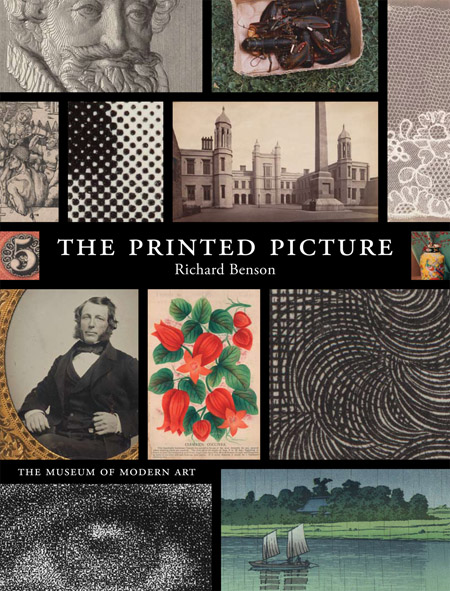

The lack of time in a photograph (which is tied in some way to the minimal influence of the artists hand in a photograph). Among others, John Berger, David Hockney and Richard Benson have tried to address this problem. A photograph contains so little time because everything is compressed into a fraction of a second (and even a "long" exposure practised by the likes of Atget out of necessity or others by choice makes very little difference to this - perhaps just a little, but not enough). As Hockney put it,

the imbalance between the two experiences, the first and the second lookings, is too extreme.2.

The frame. The window that seems to continually apply its internally focused tension, never allowing the photographic image beyond those borders - be they square, rectangular or circular, 8x10 inches or 8x10 feet. The photographic frame has frequently been regarded as a window (and often positively so). Yet as a window, all we can ever do is look through it. Never step through it like a door (or even break through it) to what is beyond.

3.

Perspectivism. Photography has for so long been limited (from long before the invention of film) by the concept of Renaissance Perspective, a theoretical straight-jacket that photography has usually been too insecure to try and throw off, never mind break from completely. It took painting 400 years. How long is it going to take photography?

(Let's Be Honest, the Weather Helped - Walid Raad - The Atlas Group Archive)(btw, do respond with your thoughts, criticisms or comments. Posts are moderated, but only because I kept getting too many spam and junk posts)