The last (?) of Anselm Kiefer's four seasons from the New York Times:

Thoughts on photography and what inspires it - books, poetry, film, art. And various other ramblings.

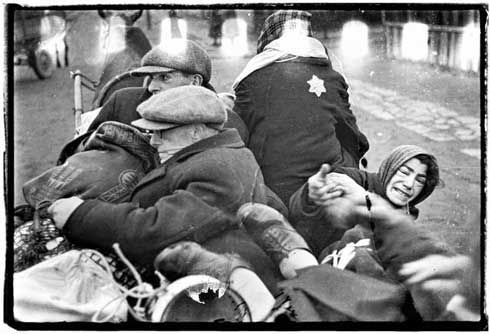

"Genewein was a skilled amateur, and his Movex 12 was confiscated from its Jewish owner. The scarce colour stock came from Agfa. Thus equipped, the accountant went into factories where hats or Wehrmacht uniforms were being made, and he stood beside the lines of Jewish children as they waited to be fed.

In much the same way as August Sander, the accountant was fascinated by the principles of visual taxonomy and social hierarchy. His subjects stand awkwardly at their workbenches, in groups or singly, glaring out of hollow eye-sockets. These anonymous Jewish workers are exhausted and helpless, and it is intolerable even to think of them being made to pose for the camera.

Genewein's self-portraits, taken in an office beside an adding machine, have the same stilted, literal quality. He is playing the role to which he believed his own status as artist entitles him. Like Hitler - who displayed a consuming interest in the precise way in which he was depicted photographically, not just at every rally, but in private, too - Genewein thinks that he represents the forces of civilisation.

And like Leni Riefenstahl's work, with the same absence of hypocrisy or misgivings, these photographs express the true nature of power. The Germans are engaged in the grand project of reclaiming Jews from their criminal, dissolute ways. The photographs are testimony to the Nazi belief in the ennobling value of labour.

Where Germans are present, as the numerous trainloads of Jews arrive, they stand slightly apart. They are the masters now, and it isn't relevant that what lies in store for their charges is not benign.There are Jewish middlemen to make the contact with the inferior race less onerous. When Himmler visits the ghetto, Genewein is at hand to record the tribute paid to him by the collaborationist Chaim Rumkowski, who ran the ghetto on behalf of the Germans. No imperial photographer would more accurately have captured the complex of emotions implied by the arrival of a proconsul in a remote outpost of Empire."... from Cold Gaze of a Nazi Camera

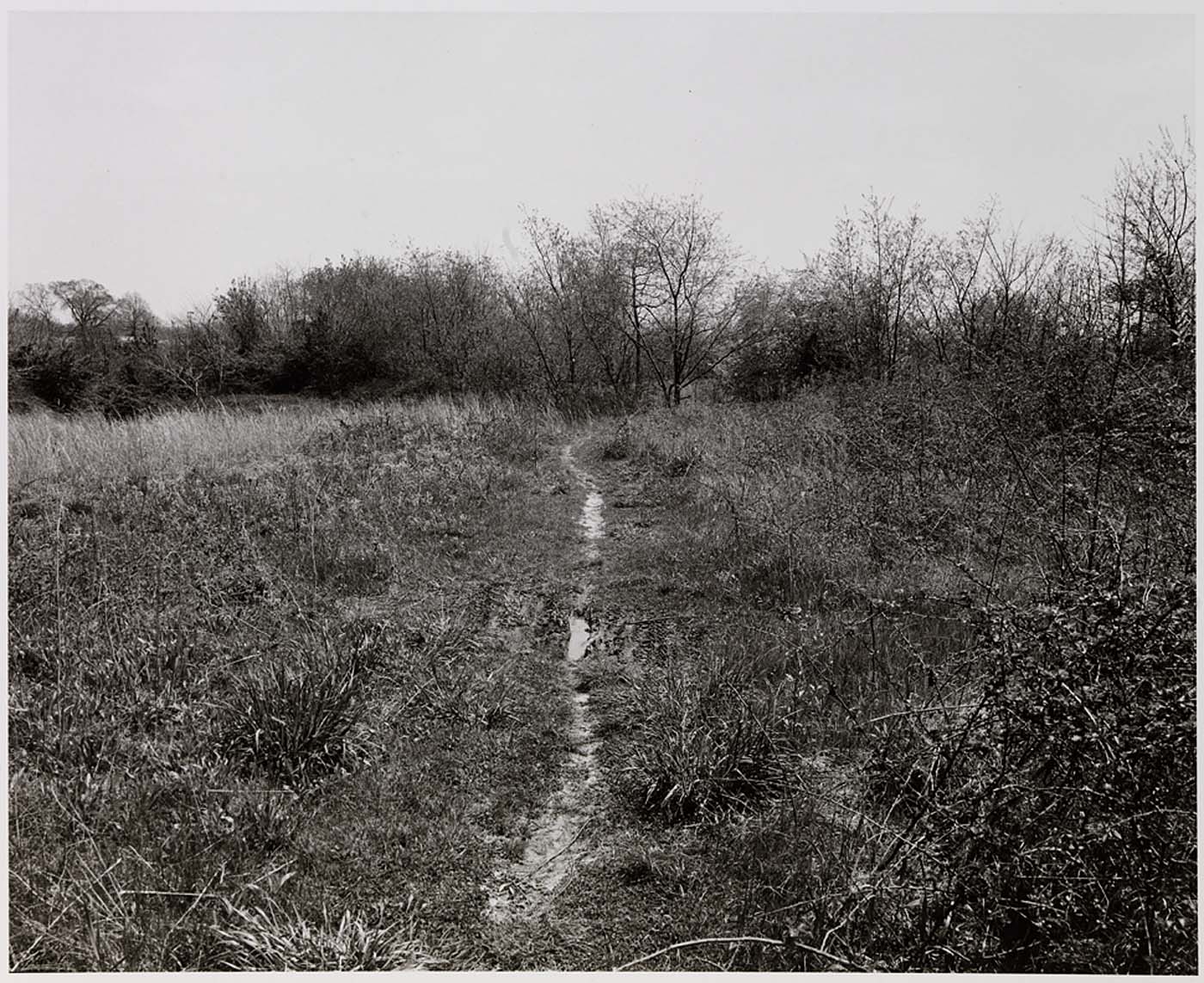

"The river's tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind

Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed."

From The Fire Sermon - The Waste Land

by T.S. Eliot(© 2006 timothy atherton)

"Snow melt in the Odenwald. Goodbye, winter, parting hurts but your departure makes my heart cheer. Gladly I forget thee, may you always be far away. Goodbye, winter, parting hurts."

(March 2010)

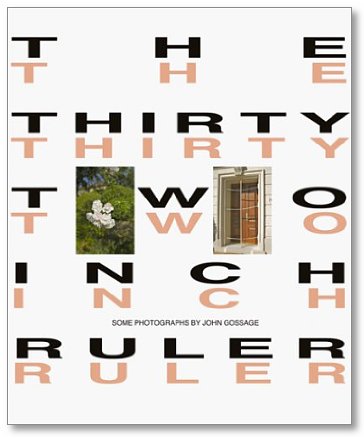

"John Gossage, the renowned American photographer and photography book-maker, presents two companion volumes and his first ever books in color. Engaged in a dance, neither book comes first, there is no hierarchy or sequence to the pair of volumes.

Gossage is one of the most literary of photographic book authors and in The Thirty-Two Inch Ruler, the narrative, whilst not autobiographical, is about a neighborhood in which he lives; one that is singular in the United States. At the same time provincial and international, it is a neighborhood populated by ambassadorial residences, embassies, and the lavish private homes of those who are in positions of power and influence in Washington. A project he began with the arrival of a new neighbor, the Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and made over a full year’s cycle of seasons, these are images from the drift of privilege. The streets, cars, homes and yards of this neighborhood are photographed on perfect spring or autumn days, with sparklingly clear blue skies, and flowers or foliage accenting the order. These are photographs about how one might wish the world to be, how beauty might be seen as desire. In the same year Gossage made the Map of Babylon, photographing digitally from Washington, to Germany, to China and places in-between. This look away, to places beyond the immediate and local, is a classic exploration of particulars of the outside world."

Up now:Luigi Ghirri - Paesaggio italiano/Italian landscape

Lee Friedlander - Factory Valleys

Sally Eauclaire - The New Color Photography and New Color/New Work

Stephen Shore - Fotografien 1973 bis 1993

Andrea Modica - Treadwell

Josef Sudek - Smutná krajina/Sad Landscape

"Considered a groundbreaking book when first published in 1985, John Gossage's The Pond remains one of the most important photobooks of the medium. As Gerry Badger, coauthor of The Photobook: A History, Volumes I and II, asserts, "Adams, Shore, Baltz--all the New Topographics photographers made great books, but none are better than The Pond." Consisting of photographs taken around and away from a pond situated in an unkempt wooded area at the edge of a city, the volume presents a considered foil to Henry Thoreau's stay at Walden. The photographs in The Pond do not aspire to the "beauty" of classical landscapes in the tradition of Ansel Adams. Instead, they reveal a subtle vision of reality on the border between man and nature. Gossage depicts nature in full splendor, yet at odds with both itself and man, but his tone is ambiguous and evocative rather than didactic. Robert Adams described the work as "believable because it includes evidence of man's darkness of spirit, memorable because of the intense fondness [Gossage] shows for the remains of the natural world." Aperture now reissues this exquisitely produced and highly collectible classic monograph. With the addition of three images and two essays, this second edition offers new audiences the opportunity to celebrate this notable work by a master photographer and bookmaker."

"EXPRESS: What does the pond represent?

GOSSAGE:The pond is a literary monologue, a narrative landscape book, character development — all of it. ... It's set in Queenstown, but a few of the shots were actually taken in Berlin. I won't tell which ones. I wanted to speak metaphorically about nature and civilization, which I realized halfway through my project. It's a work of documentary fiction. The sites are universally trivial. There are many ponds, and that one may not even be there anymore."

(my emphasis)

Mitchell is quite a wordsmith. I enjoy the way he plays with word and language and does so in a way that appears effortless. I read one comment on this book where a reader/reviewer complained about the anachronisms in it - with made me laugh out loud. A "historical novel" is basically just one big anachronism so it seems a bit of a waste of time to actually note them as you go along and then complain about them. In fact one thing I enjoy about The Thousand Autumns is the role of interpreters in it. They are fairly central to the story as they were central to the lives of both the Dutch Traders, Japanese Merchants and Japanese authorities involved with the combination of commerce and protecting Japan from the threat of Western influence. But if course everyone in the book "speaks" English. So there will be a Dutchman helping a Japanese translator find the right words to translate a phrase correctly from Dutch to Japanese - but all done in English. As are also mistakes in translation caused by different but similar sounding words or words with two different meanings - all of which are again in English. Yet you come away from reading such a passage convinced you read/heard it in Dutch and Japanese!"The year is 1799, the place Dejima in Nagasaki Harbor, the “high-walled, fan-shaped artificial island” that is the Japanese Empire’s single port and sole window onto the world, designed to keep the West at bay; the farthest outpost of the war-ravaged Dutch East Indies Company; and a de facto prison for the dozen foreigners permitted to live and work there. To this place of devious merchants, deceitful interpreters, costly courtesans, earthquakes, and typhoons comes Jacob de Zoet, a devout and resourceful young clerk who has five years in the East to earn a fortune of sufficient size to win the hand of his wealthy fiancée back in Holland.

But Jacob’s original intentions are eclipsed after a chance encounter with Orito Aibagawa, the disfigured daughter of a samurai doctor and midwife to the city’s powerful magistrate. The borders between propriety, profit, and pleasure blur until Jacob finds his vision clouded, one rash promise made and then fatefully broken. The consequences will extend beyond Jacob’s worst imaginings. As one cynical colleague asks, “Who ain’t a gambler in the glorious Orient,with his very life?”" (Official book blurb)

"...Jacob de Zoet lies in between the sprawling, mind-altering Cloud Atlas and the controlled, sensitive Black Swan Green. It is a straightforward historical novel, told chronologically and in vivid present tense. Mitchell, who recreates entire worlds with such ease one could be forgiven for assuming that he time-travels to them, and then returns to report on what he has observed and heard (in multiple tongues), moves with no less apparent effortlessness from perspective to perspective.

Jacob’s point of view dominates early on, but there are scenes set among the Japanese themselves, including sequences in a remote mountain nunnery where women are imprisoned as sex slaves. A thrilling narrative shift in Jacob de Zoet centres around that nunnery, and the novel moves away from its should-be lovers, widening out to address the emerging global politics of 19th-century imperialism. How it reconciles them in the elegiac final pages is beautiful and despairing, a quiet, perfect note on which to end.

That ending, a string of failures of “contact,” with the disappearance from history of the story’s protagonists as certain as the vanishing of Dejima itself, is deeply felt. Often overlooked by admirers of Mitchell’s daunting formal skill is the humanism, empathetic and moral, that informs his fiction. An English naval captain endures an outbreak of gout while he attempts to do his empire’s bidding in Nagasaki Bay, affecting his decisions; a Japanese magistrate, learning of an unspeakable cruelty going unchecked, ends it in the only way possible – by sacrificing his own life.

In Cloud Atlas, the theme of predation, the tendency of organisms to prey upon each other to mutual ruination, unified the six separate narratives. In Jacob de Zoet, this preoccupation is evidenced in the careful construction of the various small, overcrowded prisons – islands, nunneries, ships, homes – inside of which the characters must operate. “Why must all things,” the same gout-ridden captain laments, “go around in stupid circles?”

A writer as naturally curious, generous and able to translate an acute perceptivity to, and wonder at, the natural world as David Mitchell isn’t likely to produce a hushed, low-key novel. For some, Black Swan Green was even a little muted: Mitchell with the volume kept too low on his singular voice – or, rather, his glorious voices. Though direct in its storytelling, Jacob de Zoet marks a return to full amplitude. That means occasionally over-long scenes and one or two rambling monologues. But it also guarantees fiction of exceptional intelligence, richness and vitality"

"“For God’s sake, somebody call it!”

Has the time come to take photojournalism off life-support? After nearly 25 years in the business, agency director Neil Burgess steps forward to make the call.

...Today I look at the world of magazine and newspaper publishing and I see no photojournalism being produced. There are some things which look very like photojournalism, but scratch the surface and you’ll find they were produced with the aid of a grant, were commissioned by an NGO, or that they were a self-financed project, a book extract, or a preview of an exhibition.Magazines and newspapers are no longer putting any money into photojournalism. They will commission a portrait or two. They might send a photographer off with a writer to illustrate the writer’s story, but they no longer fund photojournalism. They no longer fund photo-reportage. They only fund photo illustration.

We should stop talking about photojournalists altogether. Apart from a few old dinosaurs whose contracts are so long and retirement so close that it’s cheaper to keep them on, there is no journalism organisation funding photographers to act as reporters. A few are kept on to help provide ‘illustration’ and decorative visual work, but there is simply no visual journalism or reportage being supported by so called news organisations.

Seven British-based photographers won prizes at the ‘World Press Photo’ competition this year and not one of them was financed by a British news organisation. But this is not just a UK problem. Look at TIME and Newsweek, they are a joke. I cannot imagine anyone buys them on the news-stand anymore. I suspect they only still exist because thousands of schools, and libraries and colleges around the world have forgotten to cancel their subscriptions. Even though they have some great names in photojournalism on their mastheads, when did you last see a photo-essay of any significance in these news magazines?

The wire services have concentrated on development of TV and internet services and focused on financial intelligence to pay the bills, rather than news as it happens. They rely on stringers and on ‘citizen journalists’ when there’s a breaking story, not professional photojournalists...

...I woke up this morning with a dream going around in my head. It was as if I’d been watching a medical drama, ER or something, where they’d spent half the programme trying to revive a favourite character: mouth to mouth, blood transfusions, pumping the chest up and down, that electrical thing where they shout “Clear!” before zapping them with 50,000 volts to get the heart going again, emergency transplants and injections of adrenalin …, but nothing works. And someone sobs, “We’ve got to save him we cannot let him die.” And his best friend steps forward, grim and stressed and says, “It’s no good. For God’s sake, somebody call it!”

Okay, I’m that friend and I’m stepping forward and calling it. “Photojournalism: time of death 11.12. GMT 1st August 2010.” Amen.

(full article here).

”“amwell | continuum” is an artist book/journal which advances the narrative of my most recent artist broadside, “carousel”, while continuing to explore the construct of memory and resolve loss. it’s only now in the completion of this book, that I recognize a sustained and underlying thread of melancholy, similar to a passing glance in the mirror on your way out the door that reflects the unseemly or the shock of hearing your voice in a recording. for me, there are delicate moments of joy represented throughout this book, as well as a kind measure of hope. there are multiple pairings observed in the layout, perhaps to suggest a lingering in the landscape and to parallel my personal impulse to do so. in addition, I’ve been compelled to experience and express time beyond chronological sequencing, the absence of time in the horizontal dimension of past and future.

in the making of books, I’m drawn to the merging of contemporary materials and media with less common and impermanent results. Nazraeli publisher and friend Chris Pichler has generously offered a broad format laser printer (weighing-in at a hulking 150 lbs.) I suspect the machine lacks an “energy-star rating” and have found that by shutting down the lights and music and turning down the heat, I can successfully print books without short circuiting the power. obviously, this limits my printing operation to daylight hours. however, the printer allows for fine reproductions where toner sits on top of cotton fiber paper and is “fused” creating a wonderful merging of mediums. While my recent publishing efforts may have something to do with deconstructing the “art book” and shifting focus from the beautiful object to honoring content and subject, I am, as many, drawn to tactile experience and a clear expression of the work in book form; using inexpensive materials and common tools while subtracting nothing of quality or value from the piece.“

”Darius Himes: Your artist books are made from appropriated books that I assume you've picked up here and there at various bookstores. When did you first start using old books as a space to work on your photographs, and what motivated you to do so.

Raymond Meeks: It’s just been within the last year that I’ve been thinking about the use of older, existing books. I’d been mounting prints to folded pages for a few years, creating small books with limited, homespun bookbinding skill. I have a sorry stack of tattered books with crusted glue, ruined in the final attempt to bind covers with pages. The use of secondhand books also seemed a decent effort towards recycling, considering the vast heap of books that rest idle on bookshelves and especially

since what I’m doing is exploratory. So little of what I do with photography and books is deliberate or intentional. Certainly, what resonates with others seems to be born out of good luck and grace.

Creatively, I thrive when I’m put in a corner and given limited resources and few options. The books I find provide portals and clues, which allow me to work with the existing title or narrative. Sometimes the dimensions are just right, or the number of pages. But I rely heavily on the inherent voice of the book and enjoy the collaboration between what the book was in its previous life and what it might become...

...DH: Could you describe for us the process of finding a book and then how you transform it? Are there clear steps along the way and does that take months? Or do you find yourself completing these objects in a weekend?

RM: Frequenting secondhand bookstores is not an obsession, but I leave myself open to discovery. I recently came across the title Minna and Myself, containing the poetry of Maxwell Bodenheim. I immediately placed my daughter in the role of Minna, and I imagined my wife using the first person voice. The book was originally published in 1918, and Bodenheim’s verse drips from the page like sap. Here are some of the lines: “Twilight pushes down your eyes, with shimmering, pregnant fingers, that leave you covered with still-born touch. With little whips of dead words”. And, “your cheeks are spent diminuendos, sheering into the rose-veiled silence of your lips”.

Needless to say, I had to use the verse sparingly, which left space for my own interpretation in pictures. This became my collaboration with Maxwell Bodenheim, who died in Manhattan in 1954. I hadn’t known of Bodenheim previous to the discovery of Minna and Myself and I imagined, in a narcissistic way perhaps, that I might renew his words. I trust that he might approve of our posthumous collaboration. I genuinely took his words to heart and spent a number of days with prints and negatives, trying to work with his pace and rhythm. In the end though, it’s just a book that’s already had a life and it’s indulgent to think about the book now in a new way. At times I feel it doesn’t exist for anyone else, really, apart from myself."

"The Muse of photography is not one of Memory's daughters, but Memory herself." John Berger

"The photograph isn't what was photographed. It's something else. It's a new fact." Gary Winogrand

"The basic material of photographs is not intrinsically beautiful. It’s not like ivory or tapestry or bronze or oil on canvas. You’re not supposed to look at the thing, you’re supposed to look through it. It’s a window.” John Szarkowski"Facts do not convey truth. That's a mistake. Facts create norms, but truth creates illumination." Werner Herzog