In last Saturday's Globe & Mail I came across a new book called Circumstances Alter Photographs (Talon Books) abut the photographs taken by Captain James Peters during the 1885 North-West Resistance/Rebellion in Canada's West. (Be sure to check out the G&M link as it may disappear behind a pay-per-view firewall)

Funnily enough I had come across these photographs a couple of years ago while researching the Metis and the Battle of Batoche and while I found them interesting I didn't twig to their wider place in photographic history (Doh - damn you tunnel vision and deadlines...).

The book is by Michael Barnholden and appears to be an extension of a thesis he wrote at Simon Fraser University.

I find these pictures fascinating for several reasons. The main one being that as far as I am aware these are the first extant photographs taken during actual combat. Unlike the earlier war photography of Fenton and the Crimea or Brady et al and the American Civil War these were taken as the fighting took place and the bullets and canon-balls were actually flying past rather than during the aftermath of battle.

Those earlier war photographers were limited by the cameras and film of the mid 1850's to taking pictures of static scenes - soldiers at rest in camp or of the dead on the battlefield after the battle was over. Of course some of this was very effective and lasting photography having eventually become iconic - Fenton's Valley of the Shadow of Death or Or Gardener's The home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg. But until cameras become somewhat smaller and more portable and film improved, photographing during battle was virtually impossible.

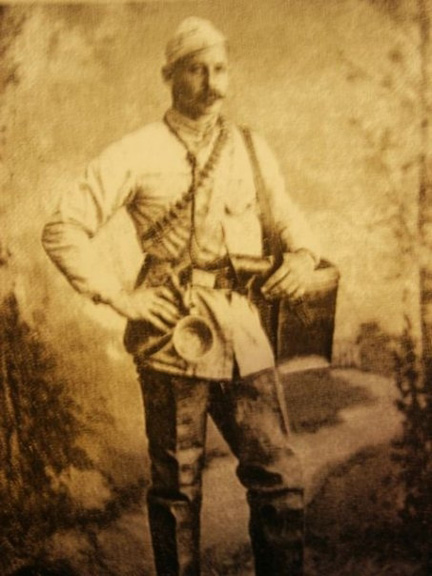

By the time Captain Peters rode into battle as part of the North West Field Force in 1885 in what is now the province of Saskatchewan, cameras and film had reached that point, just - his photographs clearly suffer from being taken hand-held, often from the saddle. And it seems that from both inexperience as well as the heat of battle Peter's admits to not being bothered too much by getting the correct exposures... Peters used a "Naturalist' Twin-Lens Camera" such as made by Rowland Ward & Co. London. But even so, these photographs show a unique aspect of what was both something of a turning point in both modern warfare and the history of Canada.

Peters was a Captain and Battery Commander in the Royal Canadian Artillery and also acted as a correspondent for the Quebec Morning Chronicle (Peters was a Militia officer) during the course of the campaign:

James Peters' first photograph of battle action at Fish Creek: He shot it from his horse as bullets whizzed around him."On Friday, April 24, 1885, Captain James Peters took the world’s first battlefield photographs under fire at the battle of Fish Creek in the Canadian Northwest Territory of Saskatchewan. As Captain of the Royal Canadian Artillery’s “A” Battery—part of the North West Field Force—he subsequently managed to expose over seventy glass plates for

the duration of the battles at Duck Lake and Batoche as well, many of them again during combat with the enemy, both on the ground and on horseback. In addition to his photographic documentation of the “Northwest Rebellion” he was also a war correspondent for the Quebec Morning Chronicle. His regular dispatches, together with his images,serve as a pioneering addition to the history of war correspondents and are presented here for the first time in their entirety.This watershed in the documentation of history was created by photographic technology, advanced to the point where “naturalist” or “detective” cameras, which came on the market in 1883, could be carried slung over the shoulder. Their faster shutter speed now allowed for hand-held photography. These cameras used coated plates that did not require preparation and could be stored for later development. Suddenly, the only restriction on any photographer was access to the action.

Neglected for over 120 years, these images literally shine new light on the War of 1885—particularly the second part of the campaign against the Indiansunder Big Bear, Poundmaker and Miserable Man. They are frankly astonishing in both their eerily haunting visual impact and as much by the mere fact that they even still exist." (From Talon Books)

The North-West Rebellion (or Resistance as it is now more often described) may not be quite so well known outside Canada, but was significant for several reasons. It was the point at which the new country of Canada decided to impose it's will on the still developing western prairies, using military force to do so. This led to the effective repression of the long established Metis (mixed raced) people of the West as a homogeneous group or people along with their established (and in many ways unique) ideas for nationhood, law and settlement. It also paved the way for the removal of the aboriginal peoples from their land and into small reservations, opening up he West to much grater settlement and as destination for immigrants.

In military terms it was a fairly short, though not initially decisive, campaign. Despite their superior numbers and equipment the Canadian force came off worse in some of the initial engagements (losing the Battle of Fish Creek) and the Metis showed themselves as effective and tough guerrilla fighters. But as the Canadian Dominion government and forces manged to effectively prevent the wider spread of the Resistance and it came to a final conflict around the community of Batoche. But even then it was no sure thing and the battle lasted for four brutal days until the Metis were defeated and their leader - Louis Riel - captured, later to be hanged.

Notable in helping turn the fight in this final battle, aside from the overwhelming numbers of Dominion troops (about 250 Metis held out against about 1,000 Canadian troops) - was he experimental use of the Gatling Gun on loan from the US Army. While it's use alone may not have been completely decisive in the battle it showed how highly effective the rapid firing weapon was, heralding the arrival of modern warfare as it moved from slow single fire weapons to such highly devastating rapid fire weapons.

The North-West Resistance - with the added impact of these photographs - is actually a fascinating look at the development of the North American Western Prairies and has everything a good (but sadly futile) story needs: a tragic but charismatic visionary leader - part poet, part mystic, part political genius; a blinkered "colonial' judiciary; a quietly brilliant guerrilla leader; a possibly crazy yet brilliant young Anglo idealist; a weak government and a Prime Minister who gives in to saving his own butt and to the power of big money; double crossing priests, deception and double agents. Ultimately, political weakness, the power of that big money - and the overwhelming power of the Canad in Pacific Railway - led to the crushing of a dream that may well have produced a very different country had it been nurtured instead of destroyed.

Finally, returning to the photographs, Barnholden takes the tittle of his book - and as the core of the ideas he develops about photography - from words Captain Peters wrote for and article in the Canadian Militia Magazine called "Photographs Taken Under Fire":

"I am convinced of one fact, and that is that no tripod instrument would for a moment survive such a trip; nor would it do for taking pictures in action, for I found that the rebel marksmen of the far West did not give an amateur photographer much time with his 'quickest shutter', and I tremble to think of the fate of the artist who would attempt to erect his tripod where the enemy possessed such a large number of 'spotters', as they call the expert riflemen of the plains. Some of them were vain enough to allow me an occasional instantaneous snap; but their desire never went so far as to allow the planting of the three sticks or the focussing with a black cloth. I marked the sighting or focus on the side for two distances, one at twelve paces (which it is needless to state was only for dead men). For the live rebels, I generally, for fear of fogging, took them from a distance, as far and as quickly as possible. All these little contrivances, and many more are necessary when one is trying to take a portrait of an ungrateful enemy. Numbers of my plates are under timed; but I am not particular. Those taken when the enemy had surrendered, and were unarmed, made better negatives, but 'circumstances alter photographs"'. (The Canadian Militia Gazette Vol I, No. 32 p252 15 December 1885)

I think the book includes a number of Peter's dispatched and letters which are in themselves quite fascinating, especially when he talks about his photography. A pdf of the earlier, thesis version of Barnholden's book can be found at the Simon Fraser University Library and includes many of Peter's dispatches as well as copies of many more of his photographs.

(btw, I haven't actually had chance yet to read the book itself - though I have looked at a number of the photographs - I'm waiting for it from the University Library here)